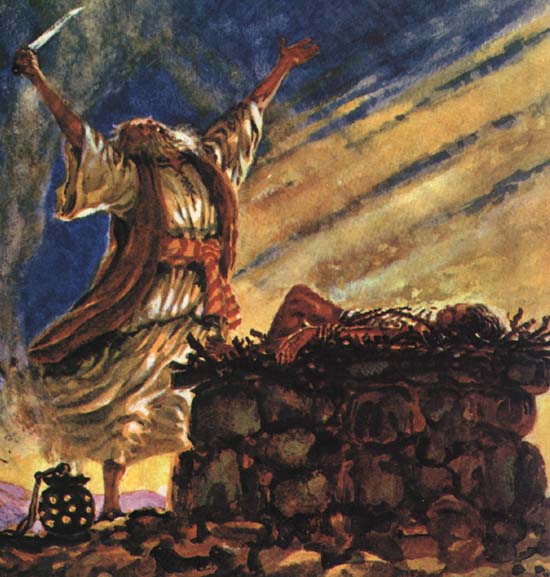

I read a feminist critique of the myth of Abraham recently – though the central point really lay in stressing the obvious fact, that in this story a man proves his virtue and his worth by his willingness to kill a child, and clearing away the mist of traditional reverence and attempts by defenders to obscure this central point.

I was reminded of this recently – reminded that the world’s two largest religions both have as a central founding myth the story of The Man Who Was Willing To Kill A Child – by reading some remarks about Lenin, written by Slavoj Zizek and quoted by Carl P. at ‘Though Cowards Flinch‘. Zizek argues that “breaking out of the deadlock” of modern left politics “should take the form of a return to Lenin.”

I was reminded of this recently – reminded that the world’s two largest religions both have as a central founding myth the story of The Man Who Was Willing To Kill A Child – by reading some remarks about Lenin, written by Slavoj Zizek and quoted by Carl P. at ‘Though Cowards Flinch‘. Zizek argues that “breaking out of the deadlock” of modern left politics “should take the form of a return to Lenin.”

Why Lenin? Because “what a true Leninist and a political conservative have in common is the fact that they reject…liberal Leftist “irresponsibility” (advocating grand projects of solidarity, freedom, etc., yet ducking out when one has to pay the price for it in the guise of concrete and often “cruel” political measures)…a true Leninist is not afraid to pass to the act, to assume all the consequences, unpleasant as they may be, of realizing his political project.”

Lenin, and the ‘true Leninist’, is responsible, not afraid –“authentic in the sense of fully assuming the consequences of his choice, i.e. of being fully aware of what it actually means to take power and to exert it.” This is why Lenin is worthy of being the Abraham of modern socialism: he proved himself serious and worthy by his willingness to ‘pay the price’ in ‘cruel measures’, to ‘assume the unpleasant consequences’, in short by his willingness to kill people.

Lenin, and the ‘true Leninist’, is responsible, not afraid –“authentic in the sense of fully assuming the consequences of his choice, i.e. of being fully aware of what it actually means to take power and to exert it.” This is why Lenin is worthy of being the Abraham of modern socialism: he proved himself serious and worthy by his willingness to ‘pay the price’ in ‘cruel measures’, to ‘assume the unpleasant consequences’, in short by his willingness to kill people.

Now, to get a good look at this we need to perform a certain inversion. Lenin and Abraham are presented as being able to recognise true reality (the will of God, ‘what it actually means to take power’) and thereby overcome personal inclination or temptation (Abraham’s love for Isaac, the “false radical Leftist’s position…which wants true democracy for the people, but without the secret police to fight counterrevolution”).

But there is no reason at all to accept that true reality was ever involved. Abraham didn’t hear the voice of God, he heard a voice in his head (if he really lived). And Lenin – well, Zizek praises him for being “not afraid…to assume all the consequences…of realizing his political project.” Realising it? But nothing was realised – the outcome of Lenin’s various ‘sacrifices’ was political despotism, industrial despotism, show trials, imperialist wars, etc. Why should we accept this ‘forced by circumstances’ line, when Lenin by all indications profoundly misread the circumstances?

So shouldn’t we, instead, suppose that these two founding fathers were willing to kill out of some personal foible, some psychological impulse that convinced them that violence was necessary? Shouldn’t we read their justifications (‘God’, ‘the revoluton’) more as symptoms? And shouldn’t we read the eulogies to them by their modern followers – Christians, Maoists, Trotskyists, Muslims, Jews and Stalinists – also as symptoms?

Consider some of what Lenin says in ‘Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder’, where he says, as Zizek does, that Bolshevism contrasts positively both with reformist opportunism, and ‘left-Doctrinairism’. He blames this ‘Doctrinairism’, this ‘irresponsibility’, on

“the petty proprietor [who] easily goes to revolutionary extremes, but is incapable of perseverance, organisation, discipline and steadfastness…driven to frenzy by the horrors of capitalism…the instability of such revolutionism, its barrenness, and its tendency to turn rapidly into submission, apathy, phantasms, and even a frenzied infatuation with one bourgeois fad or another – all this is common knowledge…It all adds up to that petty-bourgeois diffuseness and instability, that incapacity for sustained effort, unity and organised action, which, if encouraged, must inevitably destroy any proletarian revolutionary movement.”

The contours of Lenin’s complex emerge: the movement will be ‘inevitably destroyed’ by the influence of an alien tendency (that of the petty proprietor) which is ‘frenzied’, ‘driven to extremes’, ‘unstable’, prone to ‘submission’ and to ‘phantasms’, and incapable of ‘perseverence’, ‘discipline’, and ‘sustained effort’ – which is, in a word, ‘infantile’.

And then this: “the small commodity producers…surround the proletariat on every side with a petty-bourgeois atmosphere, which permeates and corrupts the proletariat, and constantly causes among the proletariat relapses into petty-bourgeois spinelessness, disunity, individualism, and alternating moods of exaltation and dejection. The strictest centralisation and discipline are required within the political party of the proletariat in order to counteract this.”

(note that here Lenin is explaining that socialism requires more than expropriating the capitalists themselves – but he doesn’t mention what proved to be the real ‘more’ that was needed, namely preventing the authoritarian development of the Bolshevik party itself. It is only ‘spinelessness’ and ‘alternating moods’ that frighten him)

As I’ve said before, psychological analysis can’t be a replacement for rational criticism – it can only show that if someone is wrong, what definite patterns of irrationality they will tend to display. But the spectacular failure of Lenin’s efforts (a failure somewhat tragic but also somewhat farcical) licenses us to suppose that he was wrong, and that an irrational factor is here playing a significant role.

What sort of pathology makes people feel a need to differentiate themselves, by the exercise of violence, from the spectre of the over-emotional, disorganised, and undisciplined? What sort of pathology drives people, under pressure, to prove themselves serious and responsible by their willingness to dominate or kill others, to impose the ‘strictest discipline’ for fear of being entirely lost?

The pathology which best fits this description, I would suggest, is patriarchal masculinity, constituted as it is by a need to distinguish oneself from women and children so as to enjoy the material and symbolic rewards of a male-dominated society.

And it’s widespread. Zizek talks about the similarity between Leninists and conservatives, who are willing to accept the burden of power. Or rather, who are driven by their psychology to invent such a burden, to find something and invent a need to be ‘tough’ on it.

Tough on crime

Tough on immigration

Tough on spongers

Tough on drugs

Tough on [enemy nation X]

Tough on opportunist class-traitors

Tough on infantile leftism

Tough on petty-bourgeois spinelessness

And right now, of course, tough on the budget: tough because of the ‘need’ to cut government spending, because of the need for ‘responsibility’ by individuals and by government.

I would submit that the last words in these slogans are of secondary importance. The important word is ‘tough’; as long as you’re tough on something, people will support you and defend you because you’re a man, and that’s profoundly reassuring.

For this reason, I would suggest, progress towards socialism depends fundamentally on the progress of feminism.

very interesting post, though we should be careful to note the distinction at play between conservatism and the Conservative party – an issue that myself and other writers at Though Cowards Flinch are debating at the moment.

It’s interesting (does Delaney discuss it?) that it’s the same Abraham who embodies the more-or-less opposite virtue in the story of Sodom, where he’s unwilling to kill even ten innocent people to destroy the wicked of the city.

She mentions it briefly to note the contrast, and the way that Abraham argues with God in the one case but says nothing in the other. But I think she argues that it’s significant that one story is a very famous, foundational myth, and the other isn’t.

This is what I gathered from your analysis: Lenin’s “spectacular failure” was that he had a debilitating stroke in 1922 and died in 1924. Yet you place the blame of everything that happened in post-1924 Russia squarely on his shoulders. Seems pretty irrational to me.

Lenin’s success is the fact that he won the revolution, while so many other Marxists (using different tactics) failed in this task. To say that Lenin achieved nothing is to ignore the fact that the Czar ever existed and that the Russian revolution ever happened. This happened regardless of the numerous crimes and industrial problems of the post-Lenin regime.

Besides, the connection between conservatives and Bolsheviks can be explained in the following way: they are both responses to liberalism (capitalism), which is the status quo of our society. Whereas conservativism is an impotent reactionary response (which does not threaten to change the capitalist structure that generates its resentment for modern ‘liberal’ society, instead opting to talk about ‘values,’ ‘morals,’ and returning to the Bible, etc.), Bolshevism’s response is more than a merely cosmetic change. It strikes at the heart of capitalism itself. This helps to understand Zizek’s famous and controversial claim that Gandhi was more violent than Hitler: while Hitler did not threaten the status quo of capitalist accumulation, Gandhi’s revolutionary effort caused a change in the very systematic structure of his society. In either case, the point is that conservatives and Bolsheviks approach the liberal status quo from the position of the outsider who sees the problems of society and demands their change. Only the former have incorrect ideas about solutions (‘we need more God in our society!’, etc.), while the latter base their worldview on a rational understanding of how capitalism works and why it needs to be overthrown.